M&A activity in the Utilities sector is expected to persist as companies strive to meet the expectations of investors, regulators and societal trends. Climate change and the focus on lowering carbon footprints will come center stage with the new Biden administration. Mizuho’s Utilities team discusses the sector’s M&A backdrop and what’s on investors’ minds. Spoiler alert: ESG will play a key role in driving premium valuations and influencing future M&A activity.

The new world order where ESG facilitates, and in many cases dictates, corporate objectives is stirring significant change within the sector. Simply put, strategic priorities are being evaluated and reset. DTE Energy, ConEd, Dominion, PSEG, and CenterPoint have announced the divestiture or spinoff of businesses that, among other things, facilitate a reduction in their carbon footprint. In October, PNM agreed to be acquired by Avangrid as a way to ensure access to capital to help meet the green objectives set by the New Mexico State Legislature. For many electric and combination utilities, the ability to effect a carbon reducing strategy will be influenced by their ability to generate regulatory support, with the impact on customer rates being a key consideration. As ESG-driven change is further embraced, industry consolidation is likely to continue with acquirers bringing capital, synergistic benefits and expertise to facilitate ESG-driven goals and energy transition.

What is driving this M&A / divestiture trend in the new world order? The old world order. Times may be changing, but the foundations underpinning transactions have not. Companies acquire others for three primary reasons: (i) they have the balance sheet but not the growth opportunity, (ii) as a cost reduction exercise to meet existing growth promises, or (iii) to position themselves to better compete in the future. Sellers do the same. Ultimately, a company’s cost of capital should influence its business decisions, but can lead management teams to ask themselves whether the strategy drives the finances or the finances drive the strategy.

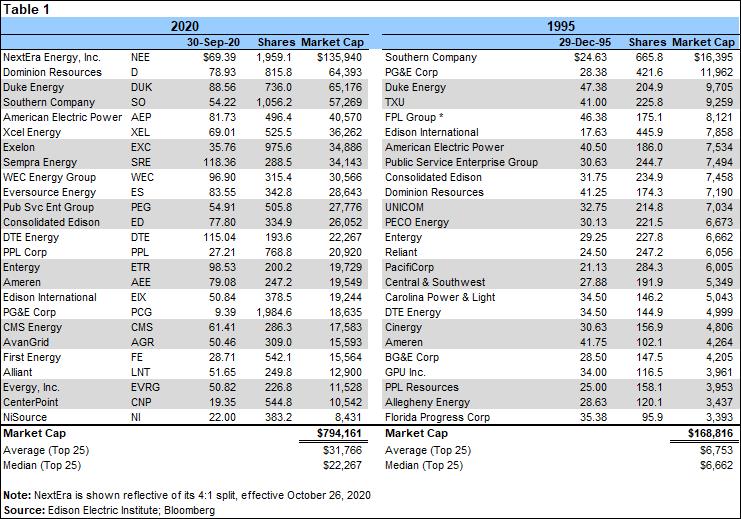

It’s Not Different This Time. Twenty-five years ago, there were 99 publicly-traded investor owned electric and combination utilities, with an average market cap of $2.652 billion. Today, there are 37, with an average market cap of $22.661 billion. The Top 25 then and now, is shown in Table 1.

Two and a half decades ago, the M&A movement in the utilities sector began in earnest, just as industry deregulation was unfolding. Deregulation came because the regulatory construct was at odds with a company being able to fully recover generation plant investment. The plants, typically nuclear, were too costly to build, but got built anyway. In exchange for recovery of that investment, many states opened their markets to competition, and companies were required to divest their expensive generation assets. Several years of M&A activity ensued.

The mergers that occurred came in all shapes and sizes and for a variety of reasons. However, the real reason most companies merged was because they didn’t have the financial wherewithal to stay independent, or they had a management team with no real visible successor or durable strategy.

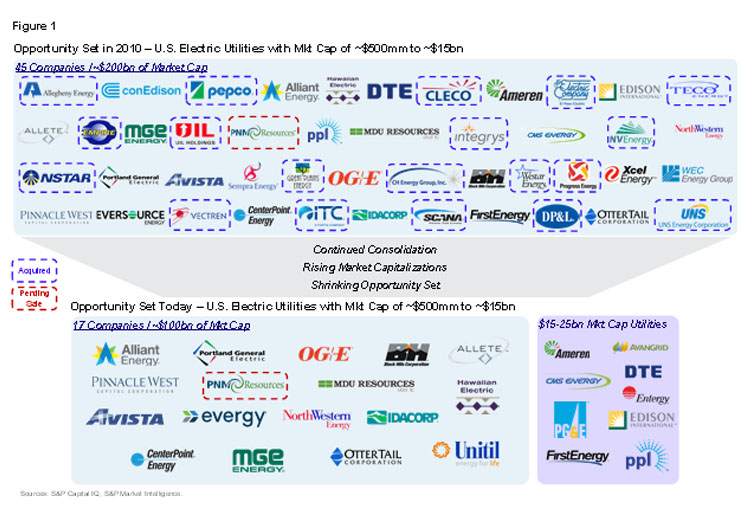

Today, the M&A play appears to be following a similar script from years past as companies execute ESG strategies. In Figure 1 below, we show the M&A opportunity set from ten years ago and today. In most cases, the opportunity set is for companies with market caps less than $15 billion. The sector has yet to see consolidation among mega caps, i.e., two companies whose individual market caps exceed $25 billion.

Does the recent flurry of non-core asset divestitures reflect corporate appetite, or lack thereof, to pursue M&A? Probably not. These non-core asset divestitures are occurring because the investment community is shying away from non-ESG friendly assets and businesses. The assets – typically midstream gas, pipeline or unregulated generation – are being viewed as impediments to underlying market valuations and, consequently, hindering the strategic alternatives that might otherwise be available to a company. Once divested, however, the fundamental need for delivering earnings growth for shareholders remains. As companies spend more to transition to a net-zero emissions profile, balance sheets and credit metrics are becoming increasingly challenged.

While the non-core asset divestiture theme has largely played out, the next theme for investors and companies may be selling peripheral utility assets (or minority interests therein) in lieu of issuing equity to fund the carbon transition. If those peripheral assets include coal or utilities with relatively slower growth profiles relative to the rest of the business, why not divest to someone that sees value in them? And, with at least $10 billion in new sector equity needed as of June 2020 (with that number likely more than doubling into 2021-2022), companies may choose this path simply to buy themselves time. That said, the fundamental issue of not being able to meet growth objectives without diluting current shareholders remains and suggests to us the resolution will lead to more sector M&A.

What’s driving this trend in the new world order? Again, the old world order. The deliverable product may be changing but the goal of attaining hurdle rates and multiple expansion has not. The lessons of Graham & Dodd and Bodie, Kane and Marcus remain alive and well. And, while these core textbooks are known to every MBA student, it’s not just about doing the deal. Two companies coming together still must overcome the realities and hurdles of getting a deal done, i.e., social issues, regulatory approvals, and valuation differentials. Perhaps that’s why Evergy is sticking with its “go it alone” approach rather than selling itself, despite reports that it has evaluated several strategic alternatives.

widt=60%

widt=60%

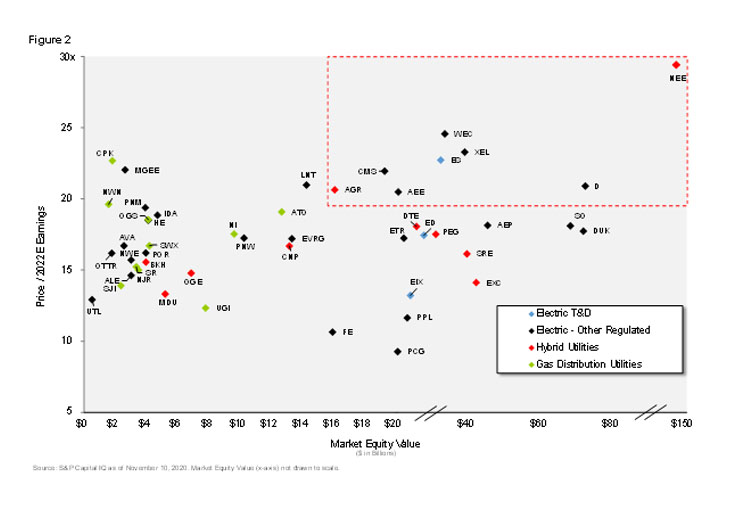

Mind the (Valuation) Gap! Today, the valuation discrepancy is quite significant and has major implications on strategic direction and cost of capital, not to mention on end-user rates. In Figure 2 above, the valuation differential by investors' views on the prospects for individual utilities is readily evident with market cap on the “x-axis” and P/E ratio on the ‘y-axis.” The spread in valuation multiples is at historically wide levels.

Companies shown inside the red box were early adopters of ESG (or themes consistent with today’s ESG themes) and are deemed to be “ESG stories.” Investors are rewarding those who’ve embraced this new paradigm with superior P/E multiples. While they may not all be clean and green currently, there is a proven track record of delivering earnings growth without disappointment, a visible path to clean energy, and favorable momentum. Additionally, many of these companies have stand-alone in-house units solely focused on ESG that report directly to senior leadership. Moreover, many either have or are putting into place compensation structures requiring executives to meet certain ESG or Key Performance Indicator (KPI) metrics as part of their year-end review.

As previously mentioned, among many drivers, one key reason PNM Resources agreed to be acquired by Avangrid is to shore up balance sheet to meet governmental policy objectives without diluting their shareholders.

Today, companies are digesting this new world order, considering the steps necessary to meet investor expectations or federal and state mandates, and formulating their plans to compete. M&A will continue as utilities with a competitive advantage seek out paths to additional growth, and those needing help realize it’s time to sell. Through this lens, we expect utility M&A to continue at a measured pace over the medium term.

What else is on stakeholders’ minds? Here are some of the opportunities and challenges corporates, debt and equity investors, financial institutions and regulators will be presented with throughout this energy transition.

Investment Indices. Consider for a moment what a NextEra / Duke linkup would have produced: a $200 billion market cap company, outpacing its nearest utility rival by $135 billion, and comprising 24.23% of the benchmark Philadelphia Utilities Index (UTY) and 0.691% of the S&P 500 (as of September 30) versus 17.61% and 0.467%, respectively if NextEra remained independent. (By comparison, Duke comprised 6.62% of the UTY and 0.224% of the S&P 500 on Sept 30.) Essentially, most investors would have no choice but to take an ownership stake in the NewCo simply to keep their portfolio balanced against the index.

ESG, Index Participation and Investment Valuations. Many portfolio managers are now being compensated based on their own ESG score. This will affect whether individual portfolio managers decide if a particular company is suitable for investment into a fund. Non-ESG centric companies will face a smaller investor pool and consequently see more share price volatility and reduced valuations. How is the retail investor impacted? It is unclear at this point, but they’ll likely have to follow the path of the institutional investor.

Financial Institution Exposure to Mega Companies. As mergers create larger companies, will banks be able to maintain the same level of absolute exposure to what a combined company may look like? Simply put, is there a risk that desired credit facilities from larger companies will require a targeted commitment from banks that may be too much either on a dollar basis or as a percentage of the industry sector? How might this be exacerbated as the number of utilities shrinks while some banks deemphasize or exit the industry for ESG reasons? It is almost certain the composition of bank groups will need to change and expand in order to support fewer and larger companies.

Will Financial Institutions Support Utilities with Exposure to Coal? Or natural gas for that matter? Increasingly, financial institutions are aligning themselves with the Paris Climate Accord or other global green initiatives. They are facing pressure from investors and environmental lobby groups regarding lending to companies not deemed to be climate friendly, and utilities are often at the forefront of this conversation. Many financial institutions have instituted glide paths to end such lending, some by as early as 2030. In addition to coal, defunding drives are taking place around institutions lending to companies involved in fracking, Arctic drilling, and virtually anything having a fossil-fuel characteristic.

Who Will Own Coal? If utilities go down the path of divesting assets they view as an impediment to reaching ESG goals, then who should or will own them? Is there room for a company that continues to operate in states (KY, WV, etc.) where the transition to clean energy will be more challenging or otherwise delayed relative to other regions?

Carbon Tax. Will we adopt federal mandates that eventually push states to change? If the impact on rates is important, will rich states be willing to subsidize poor states for moving to reduce their carbon output? Or, will we penalize those states by adopting a carbon tax? That will almost certainly produce higher rates – states and their ratepayers will either have to pay the tax or pay to transition to cleaner generation.

Role of Natural Gas. In the coming years, as the utility sector executes the energy transition away from fossil fuels to renewables and storage, will natural gas continue to serve as a transition fuel? Or will the market turn against natural gas as it has on coal in recent years? One could argue the market has gotten ahead of itself in its distaste for gas, as renewables and storage alone are unlikely to meet the energy needs of the U.S. economy for the foreseeable future.

Capital Markets Appetite. Will investors buy new issue debt or support equity offerings of carbon-heavy companies? If a company needs to raise capital, will the company be able to place it all, much less on terms that are agreeable to the company, if they still own significant carbon producing assets? Examples exist that raise concerns for certain issuers.

Regulators Can’t Be Half In. Recent events in the Pacific Northwest are a good example of regulatory egress. In late October of this year, Northwestern Corp terminated its agreement to acquire Puget Energy’s 92.5MW stake in the coal fired Colstrip Unit 4 generating facility in Montana for $1 (yes, one dollar). Northwestern had initially offered to buy the facility to take advantage of the state of Washington’s aggressive push to be all green. However, the staff of the Washington UTC then criticized the deal as providing too much benefit to NorthWestern’s customers in Montana. This is an interesting development insofar that while policy may be green, economics still play an important part. Other coal heavy states in the Midwest are likely to face similar issues in the near future, facing a balancing act between transitioning to green power and the negative economic impact such a move could have on the ratepayers regulators are supposed to protect.

The utility sector and stakeholder expectations are evolving rapidly, and currently utility companies prioritizing regulated businesses and a strong commitment to ESG and the environment are the ones being rewarded with expanding multiples and higher relative valuations. M&A will remain a key tool for utilities and shareholders looking to prosper through the continuing energy transition.

Click here for more information about Mizuho’s Power, Utilities & Infrastructure Group and Investment and Corporate Banking capabilities.