This article originally appeared in Hart Energy.

Where it begins

Just over a week before the presidential election, Mizuho Americas laid out what it saw as the likely shift in the energy policy landscape in the event of a Biden win. Nearly half a year into the Biden presidency, there is much more information to go on.

Since the inauguration, the administration has come out with an energy agenda strongly in favor of renewables, with a goal of carbon-free power generation by 2035 and a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. President Biden has placed a moratorium on drilling on federal lands, launched a review of leasing and permitting for energy development on public lands and waters, and directed federal agencies to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies when possible.

The moves were expected, but the tone out of the White House has been more strident than anticipated. There seems to be enthusiasm about the ambitious goals while at the same time only slight nods to the scale of the undertaking being proposed.

The changing landscape

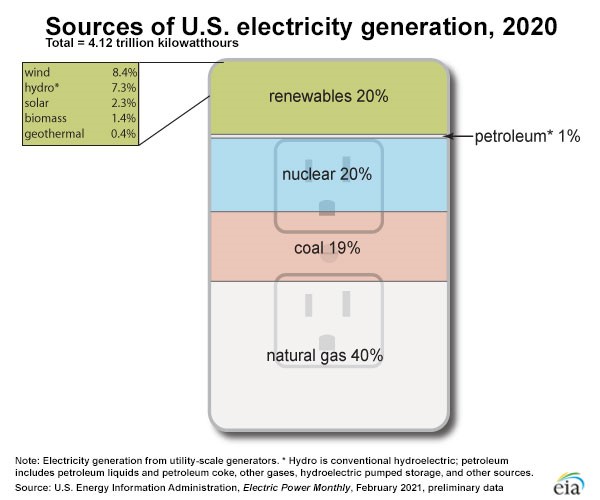

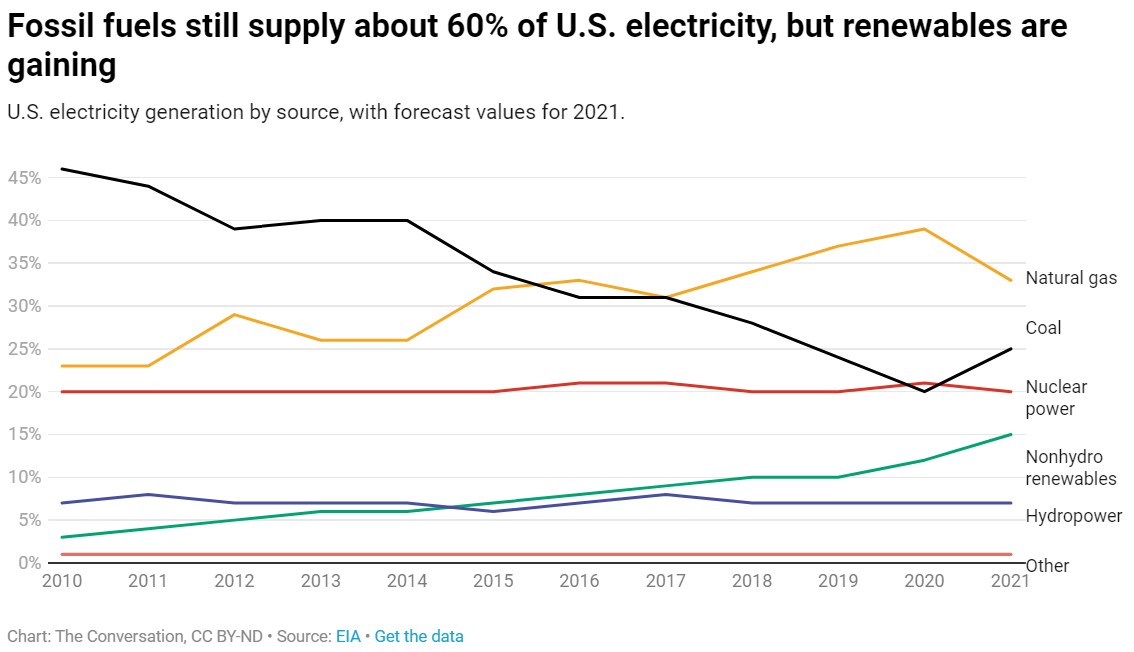

To understand the true scope of the new administration’s goals, we must understand where we are starting from. Last fall, Mizuho Americas noted our nation’s electricity production leans heavily on fossil fuels. Of the 4.12 trillion kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity the U.S. depends on, carbon-emitting fuels produce three-fifths. Nuclear power makes up another 20%, leaving renewables responsible for the remainder.

This illustrates that, despite the desire for a rapid crossover, replacing fossil fuels with renewables will be a massive undertaking to say the least. Even as wind and solar outstrips fossil fuel sources in terms of added generation capacity, the gap is immense. It will require adding or replacing over 200 billion kWh of renewable electricity production per year over the next 15 years. The challenges of this time horizon are nothing to discount. In Europe, it took 14 years to double the renewable capacity from 17% in 2005 to the 34% of generation accounted for in 2019.

And there are more opaque challenges. First, renewable energy, while not producing carbon, has some impact issues of its own. The geographic footprint solar and wind generation required to power America is vast. Solar arrays require 43.5 acres to produce a megawatt (MW) of electricity, and wind farms require 70.6 acres per MW. For coal or natural gas, those figures are 12.21 and 12.41, respectively. A recent Bloomberg article touched on this issue, noting that an average 200 MW wind farm requires spreading turbines over 19 square miles, while a natural-gas power plant with that same generating capacity could fit onto a single city block.

A Wall Street Journal article noted that solar development, and its need for land, is causing some pushback from environmental groups. Additionally, solar panels, batteries and other components require immense amounts of rare earth metals and have challenging supply chains, and both technologies come with environmental impacts unrelated to emissions.

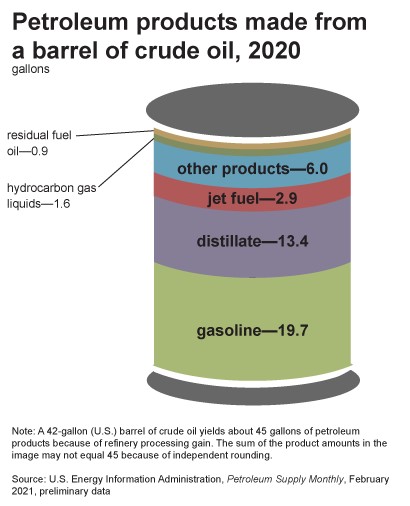

Then, there is the question of market transition. While most analyses that conclude we are in an era of rising fortunes for renewables and declining fortunes for fossil fuels look simply at costs and capacity, they leave out how integrated hydrocarbons are in the very fabric of the economy. From industrial lubricants to sandwich bags and plastics inside Tesla electric vehicles, hydrocarbons are ingrained in our everyday life. And while this does not mean we must use them for generating electricity, it does mean that there will continue to be an incentive to seek out and utilize them. Even if we successfully eliminated hydrocarbon use as a means to power transportation, it still leaves about 50% of a refined barrel of oil to be used in many other applications. (see chart, below)

Taken together, this tells us the path ahead for American renewables is unlikely to be as smooth or immediate as proponents say it will.

So, do we just throw money at it?

In response to most of these concerns, ardent renewable boosters point to the power of money; the need for “massive government investments in innovation” to bring this new world into being. And to some degree, they are correct. The scale of the investment required is significant. Wall Street calculates the transition will take $50 trillion dollars in new investment and infrastructure. That is truly a mind-bending number, even on a global scale.

But from the investor perspective, as we pointed out in October, there is no shortage of capital available in the renewable or green-energy space. The amount of capital being earmarked for green-energy and/or ESG initiatives has ballooned over the past decade. Institutional and retail investors are enthusiastic about the prospects of this transition and have allocated capital accordingly. The cash is available for green investing. Names like Bezos and Gates alone have pledged hundreds of millions of dollars and invested in initiatives as common as biodiesel, carbon capture technologies and as ambitious as fusion.

Instead of capital shortage, what investors are staring at is an opportunity problem. Many of the oft-mentioned possibilities are rooted in nascent technologies like biodiesel or hydrogen that are commercially untested, have not been proven to scale, are known to have problems, or yet to turn a profit. The shortage is not capital availability but rather suitable projects and proven technologies.

Ultimately, despite the big capital build up, the number of market-ready opportunities coming online is relatively small. What Mizuho Americas sees is a bifurcation between what is available and what can realistically provide investors an appealing return on investment.

How industry is reacting

At this point, you might be tempted to call us skeptics or worse. Not so! Mizuho Americas clients believe that ESG is inevitable, and the firm agrees. When you listen to those most affected by these goals—energy companies themselves—they will tell you they have anticipated this new regulatory environment, they understand the disconnect between the stated destination and reality, and they know they must adapt. But there are concerns about how the next 20 years play out for a few reasons.

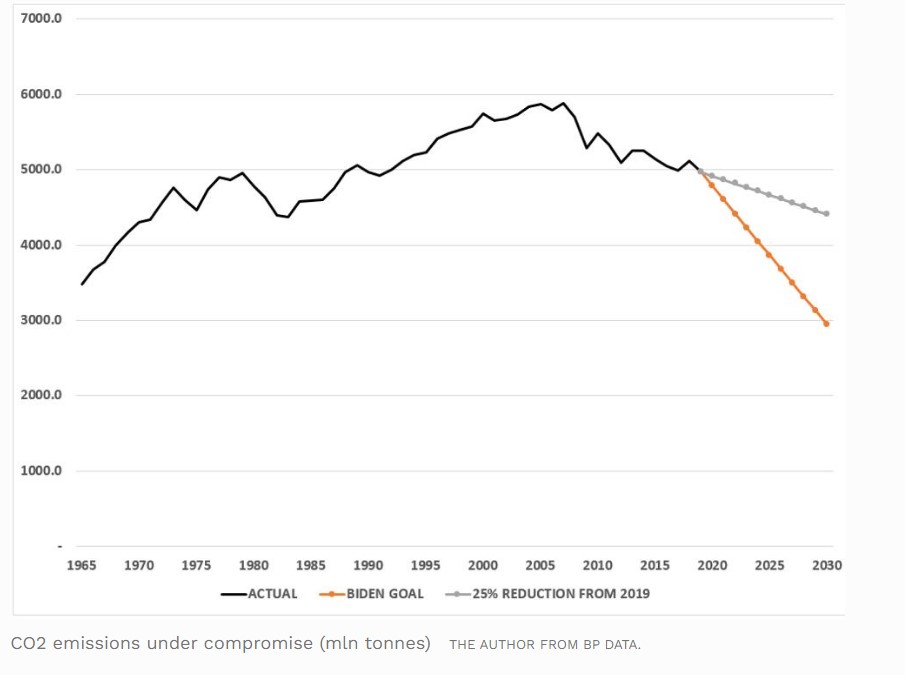

First, there is concern about setting realistic expectations. While the new administration has laid out new goals and issued executive orders, clarity is lacking. Companies feel in the dark about policy priorities and the details of the administration’s regulatory posture, which inhibits their ability to anticipate and plan. The below figure from BP shows President Biden’s goal to cut emissions by 50% from 2005 levels (the peak) and how drastic it is from current levels (and even a 25% reduction).

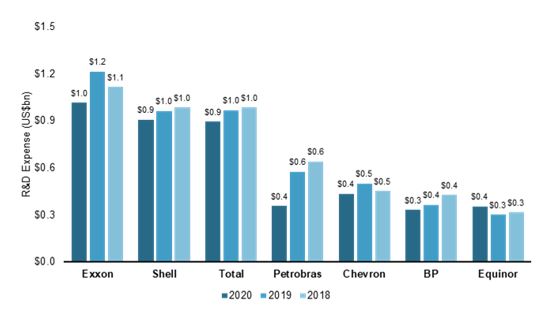

A second concern is the lack of an appreciation for how far many legacy companies have come already in terms of sustainability, efficiency and increased renewable capacity. Put simply, it is often easier to dismiss non-renewable companies as incompatible with pie-in-the-sky expectation rather than acknowledging the concrete contributions they have made and the potential future actions they are capable of.

Finally, there is little sympathy for the pressure companies are facing. With increasing tension between ESG commitments and shareholder returns, it can be hard to manage the environmental goals while remaining competitive. Put simply, navigating between opposing forces of ideological antagonists and investor sentiment makes successful, strategic management very difficult.

Reality gap

So where does that leave us? Much ink has been spilled asserting that with the right regulatory regime and enough subsidies, renewables can replace traditional generation in just 15 years. That may be true. However, we would posit there is a gap between this optimistic thinking and the reality on the ground.

Here is the Mizuho Americas read:

The transition to carbon-neutral generation and a carbon-neutral economy will happen, but it will be driven less by policymakers and more by feasibility and profitability. As technologies and strategies emerge that boost renewables and fill gaps in the market—from battery storage to carbon capture—the sector will follow those leads.

For companies in the sector, these gaps will be driven by the desires of three core groups: investors, consumers and climate/ESG advocates. They are not mutually exclusive, but it does often put them in difficult situations.

INVESTORS: When the rubber meets the road, the ROI for most ESG offerings is not spectacular when contrasted with traditional project. At present, renewables are liable to produce mid-single digit ROI, while legacy investments have double digit ROI. On top of that, many of the available renewable investment opportunities have significant hurdles or lack synergies.

CONSUMERS: The recent Texas winter freeze, and ERCOT’s struggle to adjust and prepare, brings a few challenges to light. First, when push comes to shove, reliability is paramount for consumers. Affordability is close behind. Grid resilience will be the name of the game in the short-term for consumer facing organizations, and this included the ability to flatten cost peaks and valleys. Meanwhile, widespread partisan battling is seeping into the most mundane of places, even utilities. We can expect that ideological division will continue to weigh on management teams across the energy sector. Taken together, these create a volatile mix which companies must prepare for.

CLIMATE ACTIVISTS: Companies are aware they have to manage the narrative of their activities throughout this transition, and continue to move the needle in their portfolio. Oftentimes, this will include continuing current efforts for greater efficiencies, diversifying their portfolios, and pivoting away from sectors like coal as it goes offline. Recognizing that these actors are right to push for change while communicating that change will require governments and other actors to play an active role through financial incentives and transition plans that allow companies to remain viable is imperative for success going forward.

Looking ahead: where do we go from here?

The next two decades in the energy sector will be dynamic, and at times, turbulent. The political climate is in many ways ahead of the market ecosystem. Mizuho Americas believes dialogue is one of the most effective ways of finding the path forward. In that spirit, the firm looks forward to a continued exchange of ideas as we journey together.